Westside Hotel Gives Cleveland’s Homeless a Place to Rest Their Heads During The Coronavirus Pandemic

by Ginger Christ and Rachel Dissell

Abel Currie, 63, in his hotel room in May. It’s been a relief for him to have space to quarantine safely as he searches for a permanent apartment.

The name of the hotel is kept anonymous in this story to protect the confidentiality of the guests. Print copies of this story can be found in The Cleveland Street Chronicle, sold by badged vendors at the West Side Market & downtown

A cherry-colored 10-speed rests inside the door of room 123 at a hotel on the west side. It’s overturned, forks facing the ceiling, a deflated front tire slung over a pedal. Abel Currie has crisscrossed Cleveland on the vintage bike, sometimes on a shady park trail, other times packing a lunch and heading to the lakefront. Lately, his rides have been an escape from the stresses of the coronavirus pandemic, which have created chaos, especially for those experiencing homelessness. Currie, 63, hasn’t had his own place in nearly a year, since he lost his job at the Euclid Beach Laundromat when business slowed down. But for the last few months, he’s had a bed of his own, and a television that blares old Westerns.

This hotel is home to more than 50 unsheltered individuals—those who are uncomfortable going through the county’s shelter system because of trauma or concerns about confidentiality. “I’m loving it. It’s 100% better than where I was. It’s like having my own place,” said Currie, a U.S. Air Force veteran who grew up on Cleveland’s west side.

As Covid-19 swept into Cleveland earlier this spring, advocates started looking for safe havens for those who live on the streets. Could they stay in emptied out college dorm rooms? What about vacant hotels? The task became more urgent in mid-March as public spaces like libraries, restaurants, and drop-in centers shuttered under state orders to prevent the virus’s spread. That left few places for unsheltered homeless to use the bathroom, wash up, or charge a phone. At the same time, the nonprofit Metanoia Project, which provides shelter during the winter months for those living on the streets, was preparing to shut down early.

“It’s tough enough being homeless, then Covid-19 made it harder,” Currie said.”

A Safety Strategy

Early on, Cuyahoga County and Cleveland officials and other community partners, who work to reduce homelessness in the county, made emergency plans that prioritized lowering the number of people in shelters, considered high-risk “congregate” settings by public health officials at the local and national level. They encouraged newcomers and those in the shelters to move in with friends or family and provided gift cards to assist with food costs.

The county paid to move people staying in crowded shelters or who were deemed at-risk for Covid-19 into a handful of area hotels. Anyone who tested positive for the virus was isolated in a separate hotel. The Cleveland/ Cuyahoga Office of Homeless Services’ focus was “reducing the concentration of the nearly 600 men and women who were sleeping in congregate settings as quickly as possible,” officials said in an email.

That left out the more than 200 people sleeping on Cleveland’s streets, many of whom had used shuttered drop-in centers for essential needs. The Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless (NEOCH) started planning for a larger homeless encampment, gathering up more than 50 tents and other supplies.

“We had people with no place to go,” said Chris Knestrick, executive director of NEOCH, which supports The Cleveland Street Chronicle.”

Knestrick said he asked Ruth Gillett, who heads the Office of Homeless Services, if the county would support hotels if NEOCH helped raise the money. He said she declined. “If they want to sleep outside, let them sleep outside,” she told him.

County officials said, “conversations took place with outreach workers” about individuals who were unsheltered and considered at lower risk of getting the virus. In their view, the unsheltered homeless people were “already pretty self-isolated and were not likely to have traveled on an airplane or have participated in the kinds of group gatherings that promoted transmission.”

Knestrick wasn’t opposed to an encampment, he said, at least in theory, and at the time the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had put out interim guidelines for existing encampments, though the public health agency recommended temporary individual housing, if possible. Currie was one of the people, rounded up in a parking lot, ready to sleep in the valley. He’d slept outside before, in the dead of winter. At least he’d have a tent, he figured.

Down Carter Road, near a bend in the Cuyahoga River, not far from the Centennial Lake Link Trail, Knestrick and some others scouted out a spot. The weather was still in the 40s, it had been raining, and dense fog shrouded the city. “We would have floated away down there,” Currie recalled thinking. But what choice was there?

Knestrick said he looked around and thought about how many in the encampment would be older or would have health problems that made them more at risk for complications from the virus—and death. “This is wrong of us,” he thought. “This is unethical and immoral for us to allow this to take place.” Instead, Knestrick rented 25 rooms at the hotel. NEOCH didn’t have the money to pay for the rooms, he said, but he put out a call for help.

A NEW ROUTINE

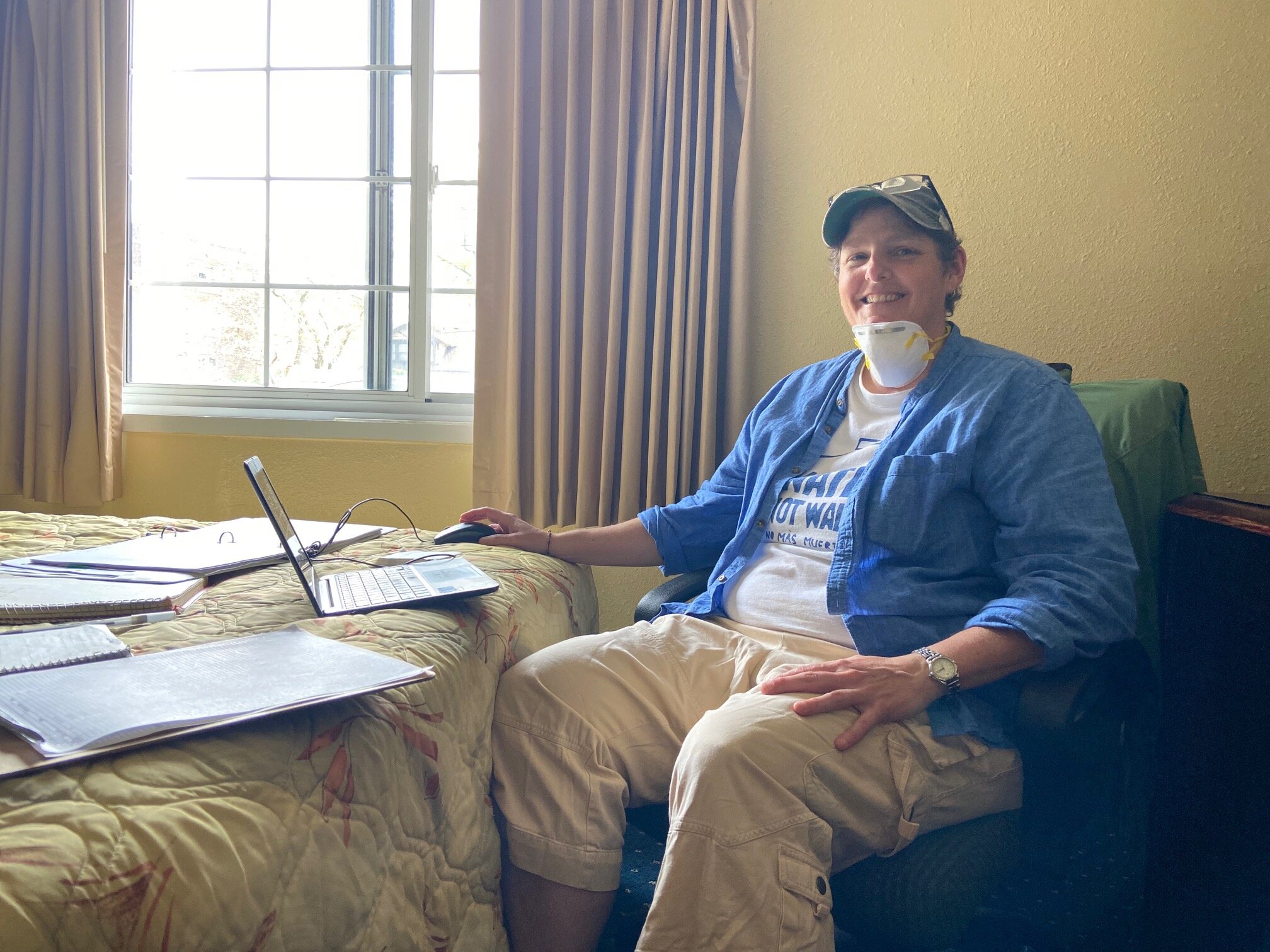

Paula Miller, who has been a Catholic Worker for two decades, uses a hotel room as her office as she coordinates hospitality and outreach efforts for about 50 unsheltered people staying at the hotel for Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless.

A little more than two months later, Paula Miller sits in a first-floor room; a hotel bed is her desk. Curls of her blonde hair peek out from under a ball cap as she updates a handwritten log passed from shift to shift by the workers hired to staff the hotel and assist the residents. Miller, a member of the Catholic Worker community, moved into the hotel with the first wave of residents, helping out along with two others, Dawn Vought and Jean Kosmac. After aiding refugees on the Mexican border in Arizona for nine months, Miller knew the importance of providing basic needs and dignity to those facing hard times.

The hotel team now has a routine that includes daily health screenings, including temperature checks for residents, distribution of meals (provided by West Side Catholic Center, Bishop Cosgrove Center, and St. Augustine), helping residents track down government stimulus checks, and filling out housing applications. Doctors from MetroHealth Medical Center come once a week to tend to medical needs, and FrontLine Services case workers visit the hotel to provide support and mental health services.

The first few weeks there was a lot to figure out about how to run what essentially became a transitional housing program overnight, all while facing a global pandemic, Miller said. For instance, out of fear of transmission, it wasn’t safe for the hotel housekeepers to come into the rooms each day to clean. So the team had to assemble cleaning kits for residents, some of whom had been living outdoors for a while, to wipe and disinfect surfaces and take out their trash.

And many of the unsheltered homeless who moved in were anxious, Miller said, because their routines were disrupted. The places they frequented for a meal, the people they checked in with, along what is often called “the trail” on the near West Side, all had shut down or disappeared.

“What people lost was their sense of community: the volunteers, the organizations, the services,” and the personal, spiritual, and mental connection it provided, she said. “That is just as vital to wellbeing as the physical stuff.”

There’s been turnover. As expected, for some shelter-resistant people, living in a hotel was too big of a change. “They weren’t used to being indoors. Some people had been outdoors so long they didn’t know how to act,” Currie said. The hotel, he said, was “like a prison to some of them.”

One resident had a mental health episode and had to be hospitalized. Another scraped up money to rent a room, where he had a small party – and then was asked to leave. Miller said NEOCH lucked out with the hotel management, which has worked closely with them, even as they remain open to the public. The hotel manager, Sarah Dontenville, said she’s taken a “figure it out as you go” approach. The 30-year-old was weeks into the job when coronavirus started to hit Ohio. As other hotels emptied out, hers filled up.

There’s been a few tough moments, Dontenville said, but she’s had those moments in her life too. At one point, years ago, she was in the same spot as some of her hotel guests, struggling with addiction with nowhere to go. “I want to see people get help,” she said. “I’m that kind of person that just cares about people.”

For Brandon S., who grew up in the western suburbs of Cleveland, the hotel gave him a roof over his head for the first time in months. “This is a blessing,” the 31-year-old said. “It’s a huge peace of mind. It keeps you out of the elements.” His hours had recently been cut at a job in litigation support he had held for 11 years, and he could no longer afford his apartment. He tried the shelter system but felt unsafe after having his belongings stolen, and instead chose to sleep outside during the winter months. Then, during the pandemic, a lot of the public showers he had relied on were shut down. “It’s been a struggle to say the least,” Brandon said. “I didn’t want to be out in the streets in February and March.”

From a public health stance, the use of hotels seems to have prevented large outbreaks of the virus in shelters by reducing the populations by more than 65% at the men’s shelter and by 58% at the women’s shelter. As of June 5, MetroHealth had screened more than 650 shelter and hotel residents for the virus, with 3.5% or a little more than 20 people, testing positive. None showed symptoms of Covid-19. At the hotel, only one person tested positive, and was moved to a different hotel to quarantine.

A wide variation in testing doesn’t allow for comparison between cities, and most states are not separately tracking Covid-19 infections among populations of people experiencing homelessness. One screening effort found more than a third of the residents in one large Boston shelter tested positive for the virus, though many had not developed symptoms. In California, which has a large population of sheltered and shelter- resistant residents, some large counties recorded relatively few cases. As of June, however, some California cities had recorded outbreaks: Los Angeles had 455 infections and 13 deaths; San Francisco had 167 - about 6% of the city’s total infections, according to the The Mercury News in San Jose.

Meeting People Where They Are

After Knestrick’s big risk, the Community West Foundation, the Greater Cleveland COVID-19 Rapid Response Fund, and a host of private donors stepped up to help cover the cost of the hotel rooms through June. The cost of the rooms and staffing the hotel with outreach workers is about $40,000 a month, Knestrick said. When NEOCH’s money ran out, the county agreed to pick up the cost of those rooms as well though its contract with Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry (LMM), supporting more than 200 rooms in total, with a capacity to house more than 380 people, depending on need. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has also paid for some of the rooms.

The hotel has offered a glimpse of what having a transitional housing environment could offer for people who might not be able to adjust from going to a shelter straight to an apartment. It was out of necessity, Miller said, that they created what is basically a low- barrier “meet people where they are” transitional-housing setting, much different from a more bureaucratic or structured setting. But she noticed that people have started to work on their future plans, whether they are getting into a rehabilitation program or finding permanent housing.

“I think people just feel supported for who they are,” Miller said. “Just accepting them and loving them. I mean, we just love them so much.” Miller said she sees value in having a middle step between the streets and permanent housing. “Not only is this a good transitional place for people to just kind of land,” Miller said, it is good training for maintaining your own space. “Really basic stuff that might be obvious to us, but if you are not used to that, and there are a lot of our folks who are not, there’s a learning curve, and they get to practice that.”

Shelter settings, because of the number of people housed, tend to have a focus on rules, which can be necessary to keep people safe, Miller said. Smaller communal settings allow time to develop relationships. Miller said she and the other staff at the hotel know each person staying in each room. That allows people the space to open up, and to think about their paths forward, instead of just where their next meal will be coming from, she said. “There’s the physical space,” Miller said “but then there’s the emotional space. And that’s what we’re able to provide. In a way, that has made this a unique setting because we’ve become a family and a community. You can’t put that into your guidelines. It’s just developed over time.” The question is whether what was an emergency decision to use the hotel has opened the door for a new possibility to address the needs of people who traditionally have been shelter resistant, instead of relying on the shelter-to- permanent housing system.

“No one really knew what we were doing here,” Miller said. “This is a unique moment in time and an opportunity to create something pretty special and use it to our fullest advantage to our folks as part of our overall goal at NEOCH to end homelessness, but also to really create a model that could be replicated or continued.”

County officials said they tried using transitional housing from 1989 through 2009 but were unable to reduce homelessness in the area or connect people with permanent housing using that approach. Officials hope to ramp up rapid rehousing assistance to people currently staying in hotels to keep shelter numbers low. “We know that hotels will not be available forever,” a county spokeswoman stated in an email.

The plan currently is for NEOCH to transition out of running the hotel— its staffing was never meant to be permanent—and to focus on its outreach to unsheltered homeless. The county has agreed to pick up the costs of the hotel rooms and staffing through the end of October and has arranged for LMM to manage the hotel.

Looking Ahead – And Back

Despite everything, the hotel doesn’t solve all of Currie’s problems. “It’s helped me greatly,” he said. “I’m not stressed out as to where I’m going to lay my head tomorrow.” But he still has a list of things to do: find a job and an apartment, hopefully on the near west or east side near bus lines and bike trails. “It’s just hard with this Covid thing. A lot of things are closed,” Currie said. “It’s hard to look ahead.”

He also has some old scars to heal, scars that date back to 1974, the year his older brother was shot and killed. Looking back, that was when 16-year-old Currie started to disconnect from his friends and from the world. He graduated from high school early. He drank and partied, eventually entering the Air Force. “I was just losing myself, I guess,” he said. “I didn’t want to face reality, so to speak.”

It took Currie many years to realize he was traumatized and didn’t know it. Now, in the midst of a global pandemic, he’s had some time–and space–to reflect.